Small Molecule Seeks To Treat Asthma Attacks

For many individuals with asthma, a tiny particle almost invisible can trigger an asthmatic attack if it enters the airways of the respiratory system. Asthma is a chronic disease that is difficult to endure. Roughly, 30 million Americans experience asthmatic attacks with 3 million having the severe and therapy-resistant form of the disease. Some cases of asthma are known to be fatal.

"Despite the prevalence of asthma around the world, therapy for this condition has not significantly changed, with a few exceptions, in the last 70 to 80 years," explains Dr. David Corry at Baylor College of Medicine. "For the most part, we are still treating the symptoms of the disease, not the underlying causes. In this work we present a novel new way to target a pathway we think is at the core of this allergic condition."

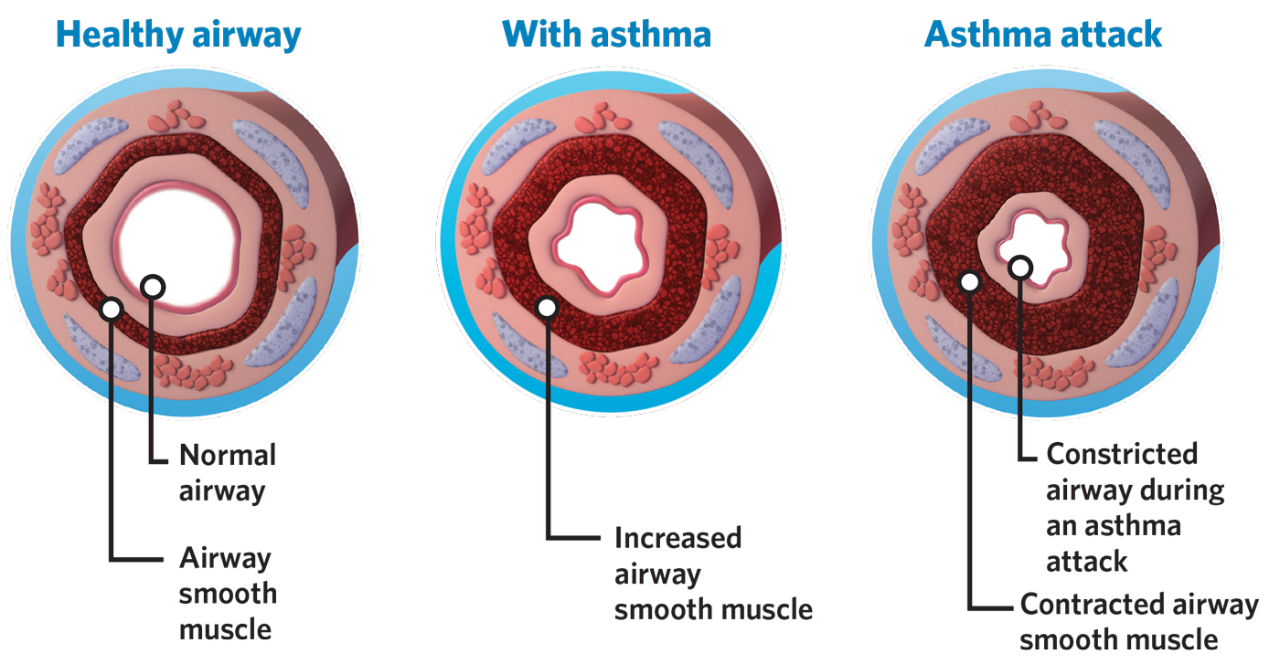

Present treatments seek to cure typical asthma symptoms, particularly the constriction of the airways so breathing becomes easy for affected individuals. Treatments also include steroids to prevent inflammation which was believed to be the underlying cause of airway constriction. Dr. David Corry's laboratory examines the molecular mechanisms that drive airway constriction.

An asthma attack is triggered when environmental factors, such as allergens, have found their way through the lungs where they work to activate a chain of mechanisms that spark the disease. Allergens activate immune cells that are then recruited to the lungs where some of them end up producing immune mediators known as cytokines. In particular, the cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 are needed for asthma to happen. These cytokines activate another molecule, known as transcription factor STAT6, which drives the expression of certain genes involved in the exaggerated contraction of the airways and caused the feared shortness of breath.

Mice that are genetically engineered to lack STAT6, will lack the responses triggered by the interactions of IL-4/IL-13/STAT6 which make them resistant to asthmatic attacks. "STAT6 is at the epicenter of the immune responses that mediate asthma, so we looked for a means to block STAT6 activation," said Dr. J. Morgan Knight, post-doctoral fellow in the Corry lab. "To activate STAT6, IL-4 and IL-13 bind to their corresponding receptors on immune cells. These receptors share a critical subunit called IL4R-alpha that activates STAT6. However, additional research from our lab has shown that completely different receptors can also activate STAT6. So, we focused our efforts on developing a small-molecule that would bind to and inhibit STAT6 activity directly."

Corry, Knight and team worked on developing a small molecule that is capable of targeting the STAT6 transcription factor without also triggering negative side effects. "After years of work, we succeeded," said Knight. "We chemically synthesized a small molecule called PM-43I that can inhibit STAT6-dependent allergic airway disease in mice. Moreover, PM-43I reversed preexisting allergic airway disease in mice with a minimum dose of 0.25 ?g/kg. Importantly, PM-43I was efficiently cleared through the kidneys and had no long-term toxicity. We concluded that PM-43I represents the first of a class of small molecules that may be suitable for further clinical development as a therapeutic drug against asthma."

An advantage to the development of the small molecule, PM-43I, is it will serve as the only treatment option that does not need to be paired with steroids.

Steroids prevent inflammation as well as other immune responses. The researchers' work shows that treating asthma with PM-43I may control asthma without impairing the ability of the body to fight pathogens. "This is important because there is a higher incidence of pneumonia in people with asthma, presumably because of the steroids they take," Corry said. "Steroids drive down all the immune system, but our small molecule specifically targets the pathway that leads to asthma, uncompromising the other pathways that allow the body to fight disease. We anticipate that patients treated with our small molecule would not need steroids as our treatment alone would be able to control the asthma. Consequently, these patients' ability to fight infections would not be affected."

Source: Baylor College of Medicine. Journal of Biological Biochemistry